Fake It Till You Mock It

There Are Mocks Among Us

"There Are Mocks Among Us," the tests whisper in the stillness. Listen closely — the truth may be hiding in plain sight.

In most cases, you can't rely on end-to-end tests alone.

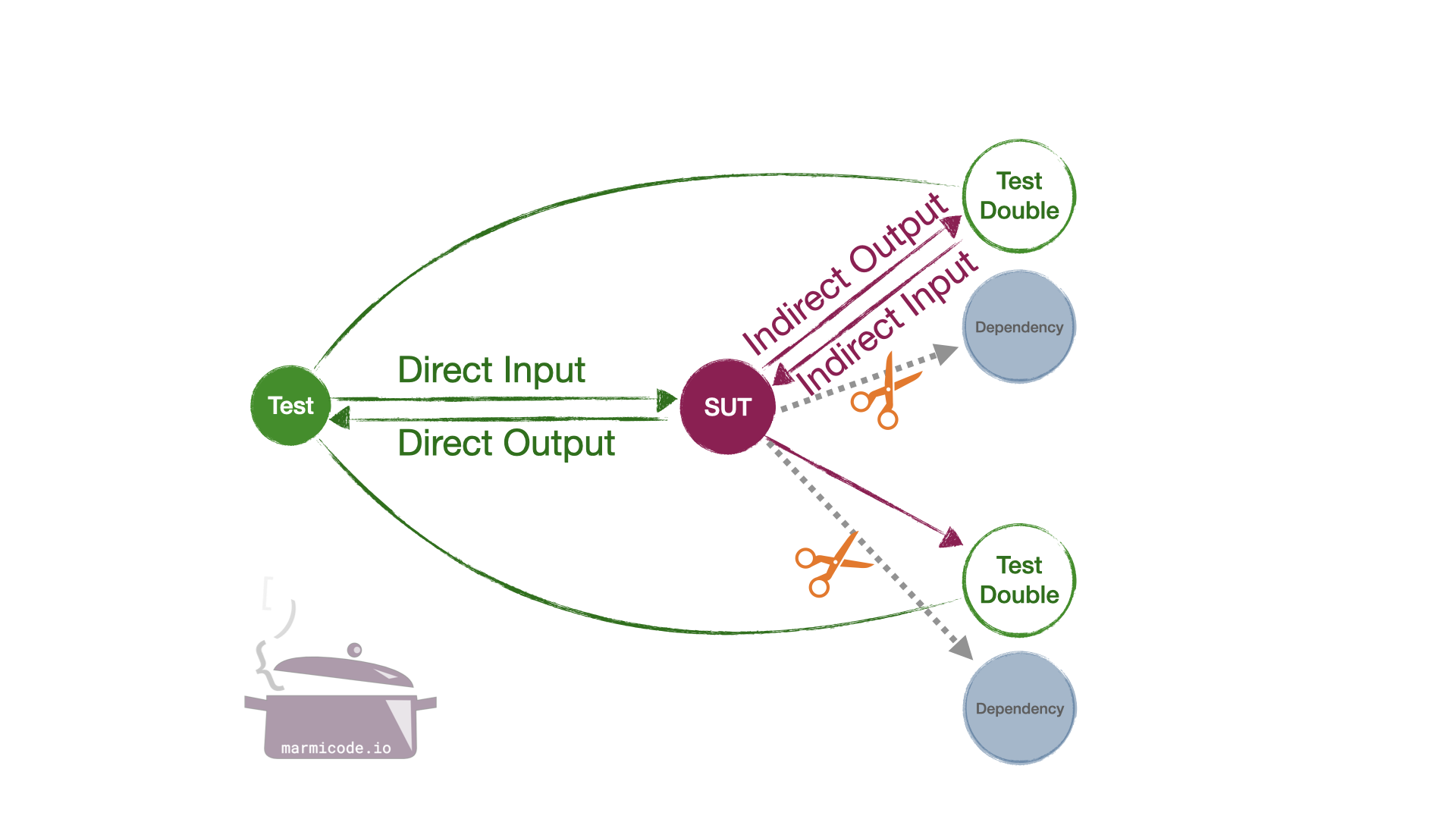

Eventually, you'll need to stop code execution from flowing through the entire app — including code you own, code you don't, the network, the database, the file system, the LLMs, and so on. You'll want to narrow down your tests to speed things up, tighten the feedback loop, gain precision, reduce flakiness, and improve overall stability.

But isolating code isn't as easy as just cutting connections. You can't sever a service and call it a day. Instead, you swap out dependencies with test doubles (e.g., mocks, stubs, spies, fakes, etc.).

And here's where the naming gets a bit messy.

It is common to refer to all test doubles as "mocks," but technically, mocks are just one kind — and believe it or not, real mocks are surprisingly rare in practice.

The Mock

A mock is a test double that's pre-programmed with interaction expectations — before the System Under Test (SUT) is even exercised, namely during the "arrange" phase of the test.

Tests written using Mock Objects look different from more traditional tests because all the expected behavior must be specified before [emphasis in original] the SUT is exercised.

— Gerard Meszaros, xUnit Test Patterns

Imagine an Angular component that fetches data — say, cookbooks — using a service called CookbookRepository.

In Vitest, a mock of the CookbookRepository service might look like this:

// Arrange

const repo: Mocked<CookbookRepository> = {

searchCookbooks: vi.fn(),

};

repo.searchCookbooks

// first call has no keywords and returns all cookbooks

.mockImplementationOnce(({ keywords }) => {

expect(keywords).toBe(undefined);

return of([ottolenghiSimple, ...otherCookbooks]);

})

// second call filters cookbooks related to "Ottolenghi"

.mockImplementationOnce(({ keywords }) => {

expect(keywords).toBe('Ottolenghi');

return of([ottolenghiSimple]);

})

// we are not expecting any additional calls

.mockImplementation(() => {

throw new Error('Superfluous call');

});

// Act

...

// Assert

...

expect(repo.searchCookbooks).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(2);

Not something you see every day, right?

You have to program the methods through the repo object to ensure they are type-safe — without having to type each method individually.

One major drawback of mocks is that a failed assertion will throw an error, which is caught by the test framework (e.g., Vitest). However, if the SUT catches the error, the test will pass and result in a false negative.

The Spying Stub

Usually — in the JavaScript world at least — when people refer to mocks, they're talking about what I call "Spying Stubs".

- They are stubs because they are programmed with return values — the indirect inputs of the SUT.

- They are spying because they track calls received for later verification — the indirect outputs of the SUT.

Here's what one looks like:

// Arrange

const repo: Mocked<CookbookRepository> = {

searchCookbooks: vi.fn()

};

repo.searchCookbooks

.mockReturnValueOnce(of([ottolenghiSimple, ...otherCookbooks]))

.mockReturnValueOnce(of([ottolenghiSimple]));

// Act

...

// Assert

...

expect(repo.searchCookbooks).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(2);

expect(repo.searchCookbooks).toHaveBeenNthCalledWith(1);

expect(repo.searchCookbooks).toHaveBeenNthCalledWith(2, {

keywords: 'Ottolenghi'

});

Note how the lack of cohesion between of the expected arguments and return values harms readability and maintainability.

Cognitive Load and High Maintenance

At first glance, using spying stubs seems straightforward — but you quickly realize that each test requires you to pause and consider:

- What is the API of the dependency?

- Which methods will be called by the SUT and need to be stubbed and/or spied on? What should they return?

- What arguments should they receive? Is it type-safe?

- Will there be multiple calls? In which order?

Mocks and Spying Stubs often over-specify tests by requiring precise interaction definitions. This makes tests structure-sensitive, increases maintenance overhead, and reduces flexibility as dependencies evolve.

For example, consider an admin dashboard for managing cookbooks. It uses a CookbookRepository which has methods such as:

updateCookbook: updates a single cookbook.batchUpdateCookbooks: updates multiple cookbooks at once.

Initially, your component uses updateCookbook, so you stub and spy on it. Later, when the implementation switches to batchUpdateCookbooks, you must update all your tests accordingly.

Instead of focusing on the SUT's behavior, you're now entangled with the API of its dependencies.

Moving on, what if you didn't participate in the development of that service? Understanding its logic becomes guesswork. You might create a Spying Stub that doesn't reflect real behavior — leading to false positives (wasting your time) or false negatives (letting bugs slip through).

Worse, if a widely-used service changes its API, you're suddenly on the hook for updating return values and argument expectations across every affected test.

Spying Stubs (or spies and stubs in general) introduce unnecessary cognitive load. Instead of focusing on the SUT, your tests become entangled with the APIs of its dependencies.

Inconsistency

Spying Stubs are prone to getting out of sync with reality.

Say you stub CookbookRepository#searchCookbooks to always return the same list. That probably means it's ignoring any filtering arguments passed to it.

It will likely not reflect any calls to CookbookRepository#addCookbook or CookbookRepository#removeCookbook.

This inconsistency can lead to false positives, false negatives, and confusing debugging sessions that will make you hate testing.

Here are some additional real-world examples where Spying Stubs can lead to inconsistencies:

- An authentication service with methods like

Auth#isSignedIn,Auth#getUserInfo, andAuth#signIn. - A cart service with methods such as

Cart#hasItems,Cart#getItems, and so on. - A repository with methods to fetch results and facets (e.g., the number of results for each potential filter), such as

CookbookRepository#searchCookbooksandCookbookRepository#searchFacets. - A geolocation adapter with methods like

Geolocation#isAllowed(which uses the permissions API under the hood) andGeolocation#getCurrentPosition.

Rarely Type-Safe

In practice, Spying Stubs are rarely type-safe.

For example, if a method is called without being properly stubbed, it might return undefined by default, leading to unexpected behavior:

cookbookRepository.search().pipe(...);

// ^ TypeError: Cannot read properties of undefined (reading 'pipe')

Even worse, if the real API changes but your stub doesn't, the tests will keep passing. You get a comforting green checkmark... and a sneaky bug in production.

The Fake

In contrast to mocks and Spying Stubs, which are programmed with specific interactions, fakes are test doubles that mimic real behavior. They are simplified versions of the real dependency.

No Special Skills or Tools Required

Fakes will only require your TypeScript skills.

You don't need to learn any new APIs or specific testing libraries or frameworks.

class CookbookRepositoryFake implements CookbookRepository {

private _cookbooks: Cookbook[] = [];

configure({ cookbooks }: { cookbooks: Cookbook[] }) {

this._cookbooks = cookbooks;

}

searchCookbooks(keywords: string): Observable<Cookbook[]> {

return defer(async () =>

this._cookbooks.filter((cookbook) => cookbook.title.includes(keywords)),

);

}

}

Consistency

Unlike mocks and Spying Stubs, the various methods and properties of a fake are generally consistent with each other.

For example, if you have a CookbookRepositoryFake that implements searchCookbooks, it will likely return different results depending on previous calls to CookbookRepositoryFake#addCookbook and CookbookRepositoryFake#removeCookbook.

Similarly, calling CookbookRepositoryFake#searchFacets will return facets that align with the results of CookbookRepositoryFake#searchCookbooks, since both rely on the same internal state of the fake.

Reusability

Since fakes mimic real behavior, they can be reused across different tests.

They often provide specific methods to configure them (e.g., the configure method in the example above), so you don't have to implement your own test double for each test.

Additionally, fakes can be reused across different testing frameworks. They can even be reused for demos or other development purposes.

Yes, you can reuse them in Storybook!

Low Cognitive Load

Fakes let you focus on what your component does, not how its dependencies work.

The fake is the only type of test double that shifts the burden of implementation and maintenance away from each test. Rather than having to create their own Spying Stubs or mocks, tests can rely on a shared fake maintained alongside the dependency by its owners — whether that's another team, a library author, or even you at a different time.

This increases the likelihood that the fake behaves like the real service, thereby reducing the risk of both false positives and false negatives.

Resilience to Structural Changes

Remember the CookbookRepositoryFake#updateCookbook vs CookbookRepositoryFake#batchUpdateCookbooks drama above?

With fakes, you don't need to worry about interactions or which method was called. You only care about the outcome.

Instead of pre-programming CookbookRepositoryFake#updateCookbook or CookbookRepositoryFake#batchUpdateCookbooks and verifying their calls, you simply check whether the cookbooks were updated in the fake:

// Arrange: set up the fake

cookbookRepositoryFake.configure({

cookbooks: [ottolenghiSimple, ...otherCookbooks],

});

// Act: Interact with the UI you are testing to update a cookbook

...

// Assert: Verify that the cookbook was updated

expect(cookbookRepositoryFake.getCookbooksSync()).toContainEqual(

expect.objectContaining({

id: 'cbk_ottolenghi-simple',

title: 'Ottolenghi (kind of) simple.',

}),

);

The test focuses on behavior rather than internal mechanics (e.g. CookbookRepositoryFake#updateCookbook or CookbookRepositoryFake#batchUpdateCookbooks), making it less brittle and easier to maintain.

Debuggability

Need to know what's happening?

With a fake — unlike mocks or Spying Stubs — you can just log something or set a breakpoint. No special tools or tricks required.

It's just you and your code.

Key Takeaways & Tips

- 🐒 Favor fakes over other types of test doubles.

- 🤷🏻��♂️ Only implement the test double APIs that are necessary for your tests.

- 🤔 Choose dependencies to replace carefully. See The Widest Narrow Test for guidance.

- 😱 If you find yourself managing too many test doubles, you might be replacing the wrong dependencies.

- 😌 Minimize the number of test doubles in a single test. A high number often indicates fragile design or overly narrow or overly wide tests.

- 💪 Ensure your test doubles are type-safe and throw errors when encountering unhandled parameters.

- 🔌 Avoid creating fakes for services you don't own. Instead, build your own adapters.

Get the Full Picture

Fakes solve one problem. See how this fits into a Full Pragmatic Angular Testing Strategy — with hands-on exercises and live guidance.

Additional Resources

- 📝 Mocks Aren't Stubs by Martin Fowler (2007)

- 📺 Fake it Till you Mock it @Ng-De by Younes Jaaidi (2024)

- 📚 xUnit Test Patterns - Refactoring Test Code by Gerard Meszaros (2007)

🍳 Related Recipes

📄️ How to Cook a Fake

A step-by-step recipe for building and using Fakes in Angular tests.